Intercepting HTTPS

From the previous exploration, one thing that was clear to me was that HTTPS requests cannot be intercepted and visualized as easily as HTTP requests. The problem is that an HTTP request gets encrypted completely the moment it leaves the browser tab (or as soon as it reaches the Transport layer of the OSI model).

[Here I am, Continuing from the last Exploration Exploring-Request-Interceptors]

This is a security feature implemented in browsers to ensure that a user’s traffic is not intercepted or modified by malicious actors in the network.

What is SSL/TLS?

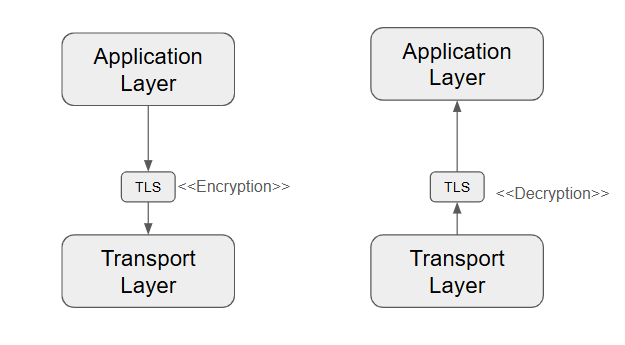

As the name suggests, SSL/TLS (Secure Socket Layer / Transport Layer Security) is a protocol that helps secure data at the transport layer (below the application layer and above the network layer. This means that encryption happens right before data enters the network layer and decryption occurs right before the data leaves the transport layer.)

PS: I initially assumed HTTPS was an application-layer protocol like HTTP. However, after some Googling and LLM-ing, I realized I was wrong. HTTP is indeed an application-layer protocol. TLS itself operates at the Transport Layer, encrypting HTTP requests before they are sent over the network. So, while HTTPS feels like it exists between the Application and Transport Layers, it is technically an Application Layer protocol that relies on Transport Layer security (TLS) for encryption.

Interestingly, there is no strict classification of HTTPS in the OSI model, as it is simply HTTP over TLS rather than a completely different protocol.

Implementing HTTPS Interception in a Proxy Server

With this understanding, I thought I had figured it all out and implemented a quick encryption/decryption mechanism in our proxy server.

Steps I assumed that would make it happen:

- Handle the HTTP CONNECT method: This ensures a TCP handshake occurs, establishing an active connection when using the proxy server in browsers.

- Decrypt the browser’s request and cache it for the data viewer.

- Encrypt the request again and forward it to the actual server.

- Receive the response, decrypt it, and cache it for the data viewer.

- Encrypt the response before sending it back to the browser.

Eazy Peazy! or so I thought. With some help from ChatGPT, I wrote the Go code and ran it.

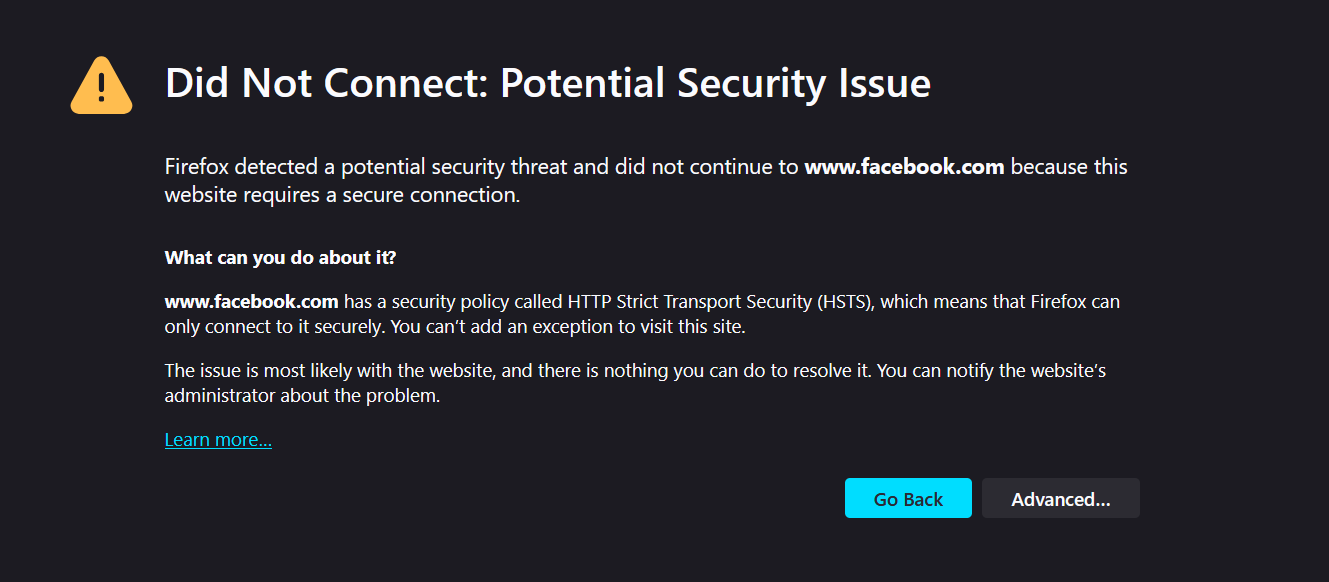

Voila! I ended up with the following error page:

Turns out, I needed to be mindful of SSL certificates.

Understanding TLS Handshake and Certificates

It makes sense, right? If it were that easy to decrypt HTTPS traffic, attackers would have already broken many secure applications!

This led me to learn more about the TLS handshake, the very first phase of TLS where:

- The server and client negotiate the TLS version (1.0, 1.1, 1.2, or 1.3).

- The server sends a Server Certificate, issued by a Certificate Authority (CA), which the client verifies.

- The client and server use Key Exchange algorithms (e.g., Diffie-Hellman, ECDHE) to securely derive a shared key.

- During the handshake, the server shares its public key (from the certificate). The client uses this only for authentication, ensuring that the server is legitimate and not an imposter.

- Post-handshake, all HTTP requests and responses are encrypted and decrypted using the derived key.

- Notable point: A common session key is derived by both the server and client, making it symmetric key cryptography.

How Certificate Validation Works

Going deeper into this, I learned about root certificates, which are issued by trusted authorities. Whenever a server sends its certificate, the browser validates it against the root certificate to determine its authenticity. Only when this validation is successful does the browser proceed with the actual HTTP request. Otherwise, it marks the connection as Not Secure!

The Chain of Trust

These root certificates are installed in the OS when a browser is installed. Examples of certificate-issuing authorities include:

- DigiCert

- Let’s Encrypt

- GlobalSign

A ServerCertificate is derived from a Root Certificate, meaning that the authenticity of a server certificate can be validated using the root certificate.

How This Works Step-by-Step

- The user installs a browser (Root Certificate gets installed with it!).

- The user visits an HTTPS website.

- The website’s server sends the ServerCertificate.

- The browser verifies the ServerCertificate against the Root Certificate.

If the root certificate is missing, the browser will mark the site as potentially vulnerable or even block access. This ensures that no one can pretend to be the website’s server. (Which makes developing an HTTPS proxy quite tricky!)

Creating My Own Root Certificate for Interception

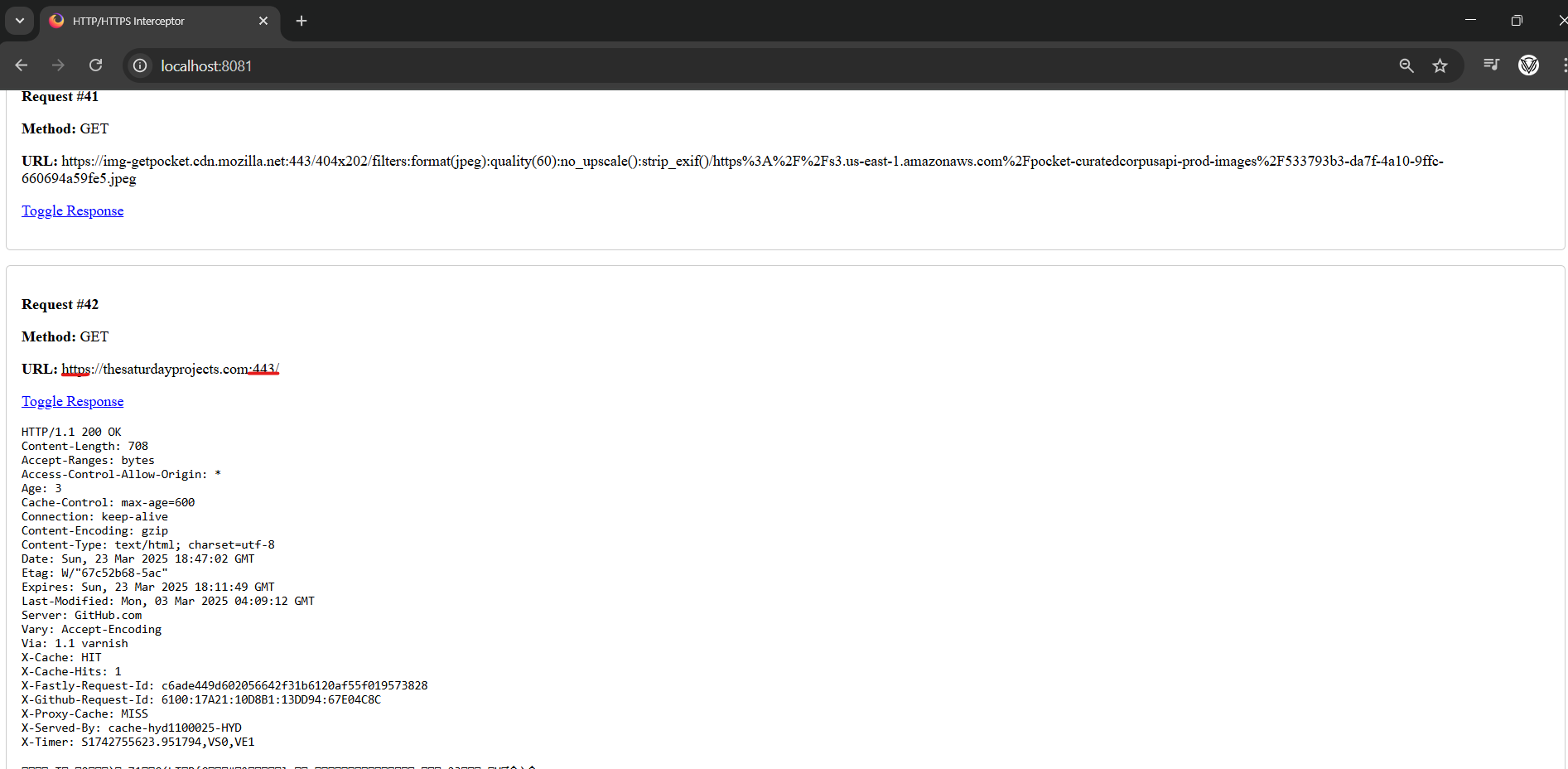

Having understood this, I ran back to ChatGPT and came up with an idea: To intercept my own requests, I could create and install my own Root Certificate!

- Used OpenSSL to generate a Root Certificate.

- Imported it into Firefox’s trust store.

- Modified my proxy server to generate Server Certificates for each website the user requests.

This allowed my proxy to act as the server, intercept traffic, and present data to the user.

Success! Here’s the Intercepted HTTPS Request for TheSaturdayProjects.com

References:

Please note that here, the main objective was to intercept HTTPS requests and understand how TLS works, rather than diving deep into the details of the TLS handshake and encryption mechanisms for different TLS versions.

If you’re interested in the unexplored aspects, you can refer to the following resources!

- Amazing videos from Computerphile:

- More on Certificates: I know I did a poor job explaining certificates—read more here.

The Code

The full implementation of HTTPS interception can be found in this repo: GitHub.

Thanks for reading from TheSaturdayProjects 🤖!